Hispanic and Cambodian Baby Black and Hispanic Baby

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Census data show that an increasing proportion of the population of the United States is of Asian or Hispanic origin. Reference curves used to narrate fetal growth relative to gestational age are predominantly based on data for White infants. The goal of this study was to compare the birth weight distributions for term Asian or Hispanic infants with that for White infants, and to decide whether the prevalence of small (SGA) or large size(LGA) for gestational age differs between Asian or Hispanic and White infants.

SETTING: A customs hospital in Northern California.

STUDY Blueprint: Data was collected prospectively from May 1 to September thirteen, 2000 on all singleton term infants born at this hospital. Gestational age was assessed by the best obstetrical approximate and ethnicity was adamant by parental report. Infants were categorized every bit White, Hispanic, Chinese, Asian Indian, Other Asian, and Other. Birth weights, length, and caput circumferences were compared using ANOVA and the Student–Newman–Keuls exam. Differences in rates of diagnosis of SGA or LGA were assessed past chi square.

RESULTS: 1539 infants were included in the study sample; 30% were White, 21% Asian Indian, xv% Chinese, 9% Hispanic, 7% other Asian, and xviii% Other. Asian (Chinese, Asian Indian, or Other Asian), Hispanic, and Other babies had lower mean nascence weights, shorter mean lengths, and smaller mean head circumferences than White babies. Asian, Hispanic, and Other male babies were lighter, shorter, and had smaller heads than white male babies. Asian females, only non Hispanic or Other ones, were lighter and had smaller head circumferences than White females; Asian Indian, Other Asian, and Other females had shorter lengths than White female infants. Indian and Other Asian, merely non Chinese, babies were more than likely than White babies to be SGA; babies in all three Asian groups were less likely than White babies to exist LGA.

CONCLUSION: Failure to account for ethnic differences in intrauterine growth may pb to inaccurate diagnosis of fetal growth abnormalities in infants of Asian ancestry.

INTRODUCTION

Abnormal intrauterine growth is a major determinant of neonatal morbidity1,two,3 and mortality.three,4,5,6 Because accurate reference information are essential to recognition of infants whose growth is not advisable for their gestational age (AGA), a number of reference curves and tables take been published, beginning with those of Lubchenco et al.4 and Usher and McLeanseven more than xxx years agone. These reference ranges typically have been based on White4,7 or predominantly Whiteviii,9 American population samples. Notwithstanding, those reference ranges may not exist applicative to minority populations, including Black,6,ten Mexican American,11 and Japanese or Chinese12 infants. Thomas et al.6 recently demonstrated that use of growth curves that do non accept race and gender into consideration may lead to inaccurate diagnosis of infants as pocket-sized (SGA) or large (LGA) for gestational age.

Census 2000 data showed significant changes in the demographics of the population in the United States. Some of these changes were specially notable in California. Between 1990 and 2000, the proportion of the California population identified as White decreased from 69% to less than sixty%, the Hispanic population jumped from 25% to 32% of the total, and the proportion of Asian origin increased from ix% to 11%.13,14 I of the greatest increases was for people of Asian Indian ancestry, who more than doubled in number, increasing their representation from 0.5% to 0.9% of the population. At our hospital, which serves an ethnically diverse middle- to high-income population, more than 40% of all alive births are at present of Asian ancestry, and more than 20% are Asian Indian infants. These changing demographics, and a subjective impression amidst members of our medical staff that infants of Asian descent tended to be smaller and were diagnosed as SGA more oftentimes than White infants, suggested that specific growth reference curves for such infants might be useful. However, nosotros were unable to locate published reference growth curves for infants of Asian Indian and Southward East Asian origin built-in in the United States. We therefore undertook this study to determine whether birth weights of term infants of those ethnic backgrounds differ from those of White infants, and if Asian or Hispanic babies were more than probable to meet criteria for intrauterine growth impairment.

METHODS

Data were collected prospectively on all singleton infants delivered at term (between 37 and 41 weeks' gestation) between May 1 and September 13, 2000 at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, California. This is a community infirmary located nigh body of water level at which approximately 4500 infants are delivered each twelvemonth. Birth weight (g), length (cm), caput circumference (cm), and sex were assessed immediately after nativity by the bedside nurse and recorded on the newborn record. Weight was measured using an electronic scale (N10 Infant Calibration, Colina-Rom/Air Shield, Batesville, IN). Length from crown to heel was measured using a paper tape after extending the legs with the infant supine on the examining table. This method is less accurate than formal anthropometric methods, but reflects usual clinical do. Head circumference was measured using a newspaper tape to make up one's mind the maximum fronto-occipital circumference. Gestational age was determined from the best obstetrical gauge. Infants were identified as SGA (weight ≤10th percentile for gestational historic period) or LGA (weight ≥90th percentile for gestational historic period) using the reference ranges provided past Alexander et al.xv

Information regarding ethnicity was self-reported by the parents on the birth document, which provides the post-obit choices: White, Black, Hispanic, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Asian Indian, Filipino, Center Eastern, Native American, Hawaiian, Guamanian, Samoan, and Other. For this analysis, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, and Filipino were grouped as "Other Asian" ethnicities, and Blackness, Middle Eastern, Native American, Hawaiian, Guamanian, Samoan, and other were grouped every bit "Other" ethnicities. Those with more than i identified ethnicity were included in the "Other" grouping, except that cases in which all ethnicities were from the "Other Asian" grouping were included in that group.

1-way analysis of variance16 was used to determine whether birth weights, lengths, and head circumferences differed amongst ethnic groups. Meaning differences between specific ethnic groups were identified using the Educatee–Newman–Keuls examination.sixteen These analyses were applied to all infants and to male and female infants separately. Differences between male person and female infants, whether for the entire sample or within each ethnic group, were assessed past Student t-test.16 Differences in the distribution of birth weights amidst SGA, AGA, and LGA categories were assessed past chi square,16 using a 6 (ethnic groups)×three (weight categories) contingency table. Differences in rates of SGA or LGA were assessed by chi foursquare using 6×two (SGA versus not SGA or LGA versus not LGA) tables. Birth weight distributions and the prevalence of SGA and LGA in each ethnic category were similarly compared with those for White infants using chi square on 2×3 or ii×two contingency tables, respectively. All data are shown as hateful±standard deviation. Significance was assumed at p<0.05.

RESULTS

There were 1659 births during the study flow. A full of 120 infants (55 who were <37 weeks' gestation, nine who were ≥42 weeks' gestation, thirty twins, and 26 for whom data on gestation or ethnicity was unavailable) were excluded from this assay. Of the included infants, 783 infants were male and 756 were female person. The number of infants in each indigenous category is shown in Table 1. The distribution of gestational ages was: estimated gestational historic period 37 weeks — 150 infants, 38 weeks — 337, 39 weeks — 517, forty weeks — 407, and 41 weeks — 128. The distribution of gestational ages did not differ between indigenous groups.

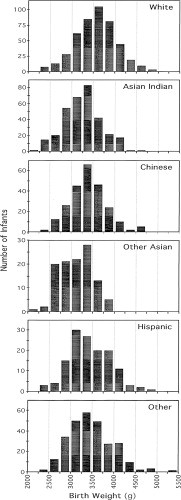

Tabular array 1 shows the hateful birth weights, lengths, and head circumferences of infants in each indigenous group. Asian (Asian Indian, Chinese, and Other Asian), Hispanic and Other infants had lower birth weights, shorter lengths, and smaller head circumferences than White infants. Female person infants had lower birth weights than male infants; this difference was largest for White and Other Asian infants and was not significant in other ethnic groups. Similarly, female person infants were shorter and had smaller head circumferences than male infants, merely these differences were non consistent for all indigenous groups. Asian, Hispanic and Other male person infants had lower birth weights, shorter lengths, and smaller caput circumferences than White male infants. Asian female infants, but not Hispanic or Other females, had lower birth weights than White female infants. The hateful length of Asian Indian, Other Asian, and Other females, but not Chinese or Hispanic females, was shorter lengths than that of White females. All Asian females, just non Hispanic or Other females, had mean head circumferences smaller than that of White females. The distribution of birth weights for each indigenous group is shown in Figure 1.

Distribution of nascency weights for infants in each ethnic grouping. Hateful nascency weights were significantly lower in each of the other indigenous groups than in White babies.

A total of 132 infants (eight.6%) were identified as SGA and 186 (12.1%) were LGA (Table 2). These rates of SGA and LGA did not differ significantly from the expected rates of 10% in each category (χ ii=4.75, p=0.09). Chi-foursquare testing demonstrated a strong human relationship betwixt the proportions of infants in these categories and ethnic group (χ ii=ninety.five, p<0.0001). For babies of Asian origins, the distribution of infants among these birth weight categories was significantly different from that for White babies, whether these groups were considered separately (p<0.002 for each comparison) or collectively (χ ii=62.6, p=0.0001). Babies in all iii Asian groups were less likely than White babies to be LGA (p<0.001 for each comparison), merely only Asian Indian and Other Asian (not Chinese) babies were more probable than White babies to be SGA (p<0.001 for each comparison). The prevalence of SGA in those groups was more than three times that amongst White infants. Compared to White babies, a greater fraction of Hispanic babies were SGA and a smaller proportion were LGA, but these credible differences were not statistically pregnant. The distribution of infants among these weight-for-gestational-historic period categories did not differ between White and Other babies.

Word

Identification of abnormal intrauterine growth is an important component of assessment and management of newborn infants, because both infants who are SGA and those who are LGA have increased rates of morbidityi,two,3 and mortality.3,four,5,6 The studies that defined this relationship between outcomes and aberrant growth patterns were based on populations that were predominantly White orBlack and White, with few subjects from other ethnic or racial groups.17 As it has become apparent that the distribution of nascence weights is different in not-White populations, the criteria for and implications of diagnosis of abnormal intrauterine growth in minority populations have come up into question. In particular, the lower mean birth weight for gestational age and higher prevalence of small size for gestational age amidst Blackness infants in the Usa has been recognized for many years,9,18 and may contribute tothe disproportionately high infant bloodshed rate for that population.xix However, use of reference curves appropriate for White infants may result in inappropriate diagnoses of minor size for gestational age among Black infants.six These relationships have been less extensively studied in other American ethnic or racial minority populations. Because of concern that failure to recognize such differences in nascence weight distributions for Asian and Hispanic infants might pb to inappropriate diagnosis of SGA among infants in those indigenous groups built-in at our hospital, nosotros undertook this investigation.

Our analyses confirmed that the birth weight, length, and head circumference are significantly influenced by both ethnicity and gender. In our sample, White infants were heavier, longer, and had larger heads that Asian, Hispanic, and infants in the Other ethnicity group. Others take previously reported that the mean birth weights of Chinese Americantwenty and Japanese American (included in the Other Asian grouping in this analysis) infants born at term, either separately12 or every bit a pooled cohort,21 were lower than that of White American infants. Alberman22 and Wilcox et al.23 accept described lower hateful nascence weights for children born to immigrants from the Indian subcontinent to the United Kingdom in comparison to infants of European origin. We are not enlightened of previous reports of like information for infants built-in to families of Asian Indian ancestry in the U.s.. In dissimilarity, previous studies accept not consistently demonstrated significant differences between the nascency weight distributions for Hispanic and White infants.6,24,25 This apparent deviation with our results may be explained by the observation of Overpeck et al.11 that Hispanic infants born at 30 to 37 weeks' gestation were heavier than White infants, but those born at 37 to 42 weeks, like those included in this analysis, were smaller than White infants. Every bit noted in a number of previous reports,vi,9,10,26 we besides found that female infants as a group are smaller, shorter and have smaller caput circumferences than male infants. These gender differences were not evident in all ethnic groups, however. We did not notice pregnant differences between male and female Hispanic infants in whatever of these measures of fetal growth, for case. This result contrasts with the finding of Cazano et al.10 that Hispanic females had significantly lower weights, shorter lengths, and smaller head circumferences than their male person counterparts. This difference may outcome from differences in the ethnic origins of "Hispanic" subjects, as those included in Cazano's study from New York Urban center were probably mostly of Puerto Rican, but those in our California sample were predominantly Mexican. Our observations are therefore generally consistent with previous reports, and support the exclamation that race and gender specific standards are necessary for diagnosis of intrauterine growth abnormalities. Because of the relatively pocket-size number of infants in our study population, these observations are limited to infants at term (37 to 42 weeks' gestation). Although the sample size was sufficient to demonstrate differences in mean birth weights at term, the number of preterm infants born during the study flow was not sufficient for either evaluation of differences in fetal growth rates before term or to establish reference ranges for infants in these minority groups. Accomplishment of those objectives volition require a much larger, population-based written report.

Infants are often classified at birth as SGA, AGA, or LGA past plotting their nativity weight on standard growth curves that were developed in Denver in the 1960s.4,7 Because employ of those curves appears to overestimate the number of infants who are SGA (≤tenth percentile) and overestimate the number who are LGA (≥90th percentile), the more recent data from the national 1991 birth accomplicexv were used to categorize infants as SGA, AGA, or LGA for this analysis. The overall distribution of infants in our multiethnic sample, with 8.6% SGA and 12.i% LGA, was not different from the expected proportion of 10% in each of those categories, indicating that these contempo national standards were appropriate to our population in its entirety. Yet, compared to White neonates, term Asian babies were significantly less likely to exist labeled equally LGA and Asian Indian and Other Asian (simply not Chinese) term infants were significantly more likely to be identified as SGA. Failure to demonstrate an increased rate of SGA among Hispanic infants despite their significantly lower mean nascence weight may exist a consequence of the small sample size for this indigenous group. A larger survey volition exist required to resolve that question.

Other investigators have noted significant differences between the nativity weight distributions of infants born to foreign-born immigrant women and those of infants built-in to U.South.-built-in women of the aforementioned ethnic origin. David and Collins found that infants of African-born Black women, unlike those of U.S.-built-in Black women, had a nascency weight distribution and gamble of low birth weight similar to infants of U.S.-built-in White women.29 Both Cervantes et al.25 and Guendelman et al.30 institute that immigrant Mexican women had a significantly lower risk of low nascence weight than native-born non-Hispanic White women. The risk of prematurity was also significantly lower among immigrant women in the latter two studies. None of these studies specifically addressed differential rates of intrauterine growth disturbances. The majority of the Asian Indian and Chinese infants in this cohort were born to first-generation, middle-to high-income, good for you immigrants employed in the high-technology industry. Specific information regarding the mother'southward state of nativity was not recorded for this analysis, however, limiting the utility nascence weight distribution in this pocket-size sample for evaluation of fetal growth in these ethnic groups. In addition, the typical high level of teaching amidst Asian immigrants whose infants are born at our hospital make it likely that they constitute a nonrepresentative sample, so data gathered from such immigrant populations also cannot exist extrapolated to the population of their respective countries of origin. Because it is non clear that normative data for infants born to kickoff-generation immigrants is appropriate for evaluation of intrauterine growth of infants in subsequent generations, it may be necessary to include maternal state of nascency (i.eastward., U.South. or foreign) in future studies of the human relationship betwixt ethnicity and birth weight distributions.

Infants from minority groups may be at increased take chances for morbidity or mortality by virtue of their lower nativity weights. Alternatively, information technology may be that these infants are smaller merely because of ethnic or racial factors. In that case, utilize of the growth curves advisable for White American infants might lead to inappropriate diagnosis of many infants as SGA. If merely those term infants with birth weights less than the 3rd percentile are at increased gamble, as reported by McIntire et al.,3 those infants will be erroneously identified as being at the high risk for perinatal complications or mortality. Conversely, it may exist that increased gamble extends to college birth weight percentiles for infants in some minority groups. Our observations, and similar reports from other sources, suggest that normative data on nascency weight distributions specific to each gender and ethnic grouping, and possibly for first-and subsequent-generation immigrants, are needed. In addition, the relationships between adverse perinatal outcomes and nativity weight need to be independently defined for each of these groups.

References

-

Doctor BA, O'Riordan MA, Kirchner HL, Shah D, Hack Yard . Perinatal correlates and neonatal outcomes of modest for gestational age infants built-in at term gestation Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001 185: 3 652–9

-

Kramer MS, Olivier M, McLean FH, Willis DM, Usher RH . Affect of intrauterine growth retardation and body proportionality on fetal and neonatal outcome Pediatrics 1990 86: 5 707–xiii

-

McIntire DD, Flower SL, Casey BM, Leveno KJ . Birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality amongst newborn infants N Engl J Med 1999 340: 16 1234–eight

-

Lubchenco LO, Hansman C, Boyd Due east . Intrauterine growth every bit estimated from liveborn birth-weight data at 24 to 42 weeks of gestation Pediatrics 1963 32: 793–800

-

Battaglia FC, Lubchenco LO . A applied classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age J Pediatr 1967 71: two 159–63

-

Thomas P, Peabody J, Turnier V, Clark RH . A new look at intrauterine growth and the bear on of race, altitude, and gender Pediatrics 2000 106: ii E21

-

Usher R, McLean F . Intrauterine growth of alive-built-in Caucasian infants at sea level: standards obtained measurements in 7 dimensions of infants built-in between 25 and 44 weeks of gestation J Pediatr 1969 74: 6 901–10

-

Babson SG, Benda GI . Growth graphs for the clinical assessment of infants of varying gestational age J Pediatr 1976 89: 5 814–20

-

Brenner WE, Edelman DA, Hendricks CH . A standard of fetal growth for the U.s.a. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1976 126: v 555–64

-

Cazano C, Russell BK, Brion LP . Size at birth in an inner-city population Am J Perinatol 1999 16: x 543–8

-

Overpeck MD, Hediger ML, Zhang J, Trumble AC, Klebanoff MA . Nascence weight for gestational historic period of Mexican American infants built-in in the Us Obstet Gynecol 1999 93: vi 943–7

-

Wang X, Guyer B, Paige DM . Differences in gestational age-specific birthweight among Chinese, Japanese and white Americans Int J Epidemiol 1994 23: 1 119–28

-

U.S. Census Bureau. 1990 Demography Lookup In: U.S. Section of Commerce 1991

-

U.S. Census Bureau. Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics In: U.South. Department of Commerce 2001

-

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M . A United states of america national reference for fetal growth Obstet Gynecol 1996 87: 2 163–8

-

Glantz SA . Primer of Biostatistics 3rd ed New York: McGraw-Loma 1992

-

Goldenberg RL, Cutter GR, Hoffman HJ, Foster JM, Nelson KG, Hauth JC . Intrauterine growth retardation: standards for diagnosis Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989 161: 2 271–7

-

Freman MG, Graves WL, Thompson RL . Indigent Negro and Caucasian birth weight–gestational age tables Pediatrics 1970 46: one 9–15

-

Alexander GR, Tompkins ME, Altekruse JM, Hornung CA . Racial differences in the relation of birth weight and gestational age to neonatal mortality Public Health Rep 1985 100: 5 539–47

-

Yip R, Li Z, Chong WH . Race and birth weight: the Chinese example Pediatrics 1991 87: five 688–93

-

Williams RL . Intrauterine growth curves: intra- and international comparisons with different ethnic groups in California Prev Med 1975 four: two 163–72

-

Alberman Due east . Are our babies becoming bigger? J R Soc Med 1991 84: 5 257–sixty

-

Wilcox M, Gardosi J, Mongelli Thou, Ray C, Johnson I . Birth weight from pregnancies dated by ultrasonography in a multicultural British population BMJ 1993 307: 6904 588–91

-

Aguilar T, Teberg AJ, Chan L, Hodgman JE . Intrauterine growth curves of weight, length, and caput circumference for a predominantly Hispanic infant population Public Health Rep 1995 110: 3 327–32

-

Cervantes A, Keith 50, Wyshak K . Adverse birth outcomes among native-born and immigrant women: replicating national evidence regarding Mexicans at the local level Matern Child Health J 1999 three: 2 99–109

-

Arbuckle TE, Wilkins R, Sherman GJ . Birth weight percentiles by gestational age in Canada Obstet Gynecol 1993 81: one 39–48

-

Guaran RL, Wein P, Sheedy M, Walstab J, Beischer NA . Update of growth percentiles for infants born in an Australian population Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 1994 34: 1 39–50

-

Zhang J, Bowes WA Jr . Nascency-weight-for-gestational-age patterns by race, sexual activity, and parity in the Usa population Obstet Gynecol 1995 86: ii 200–8

-

David RJ, Collins JW Jr . Differing birth weight among infants of U.S.-born blacks, African-born blacks, and U.S.-born whites N Engl J Med 1997 337: 17 1209–14

-

Guendelman Southward, Buekens P, Blondel B, Kaminski 1000, Notzon FC, Masuy-Stroobant G . Birth outcomes of immigrant women in the Us, France, and Belgium Matern Child Health J 1999 3: 4 177–87

Author information

Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Madan, A., Holland, S., Humbert, J. et al. Racial Differences in Birth Weight of Term Infants in a Northern California Population. J Perinatol 22, 230–235 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7210703

-

Published:

-

Event Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1038/sj.jp.7210703

Further reading

bowserdenteoffores.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/7210703

0 Response to "Hispanic and Cambodian Baby Black and Hispanic Baby"

Post a Comment